Dr. James S. Taylor

THE IMPORTANCE OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE – THE GOOD BOOKS

PREFACE

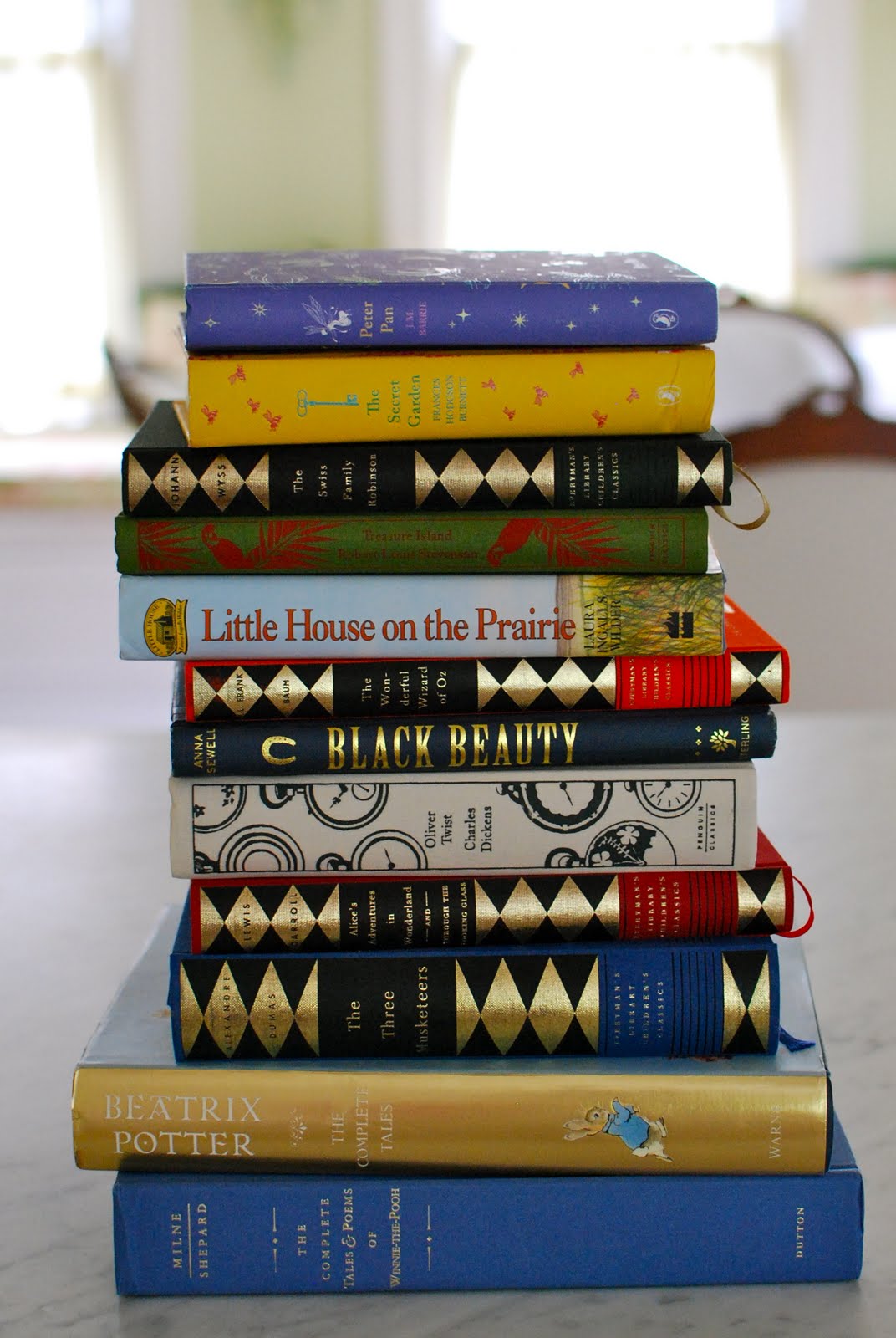

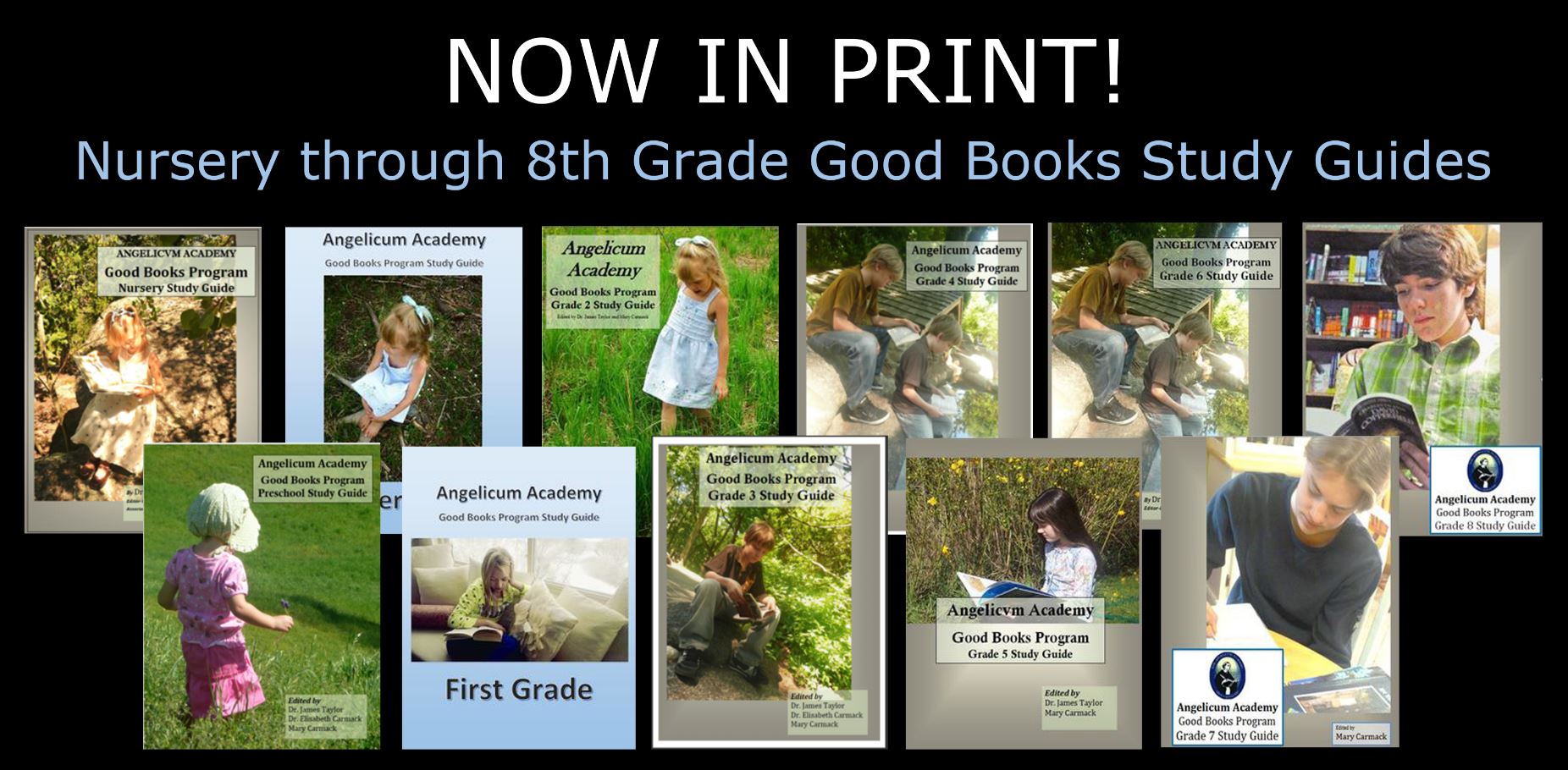

The list of books followed in this collection and the suggested ages for their reading, is taken from the list of Good Books selected by Dr. John Senior. Dr. Senior was the brilliant professor of classics and humanities at the University of Kansas who with two colleagues – Drs. Dennis Quinn and Frank Nelick – taught the influential Integrated Humanities Program (“IHP”) for freshmen and sophomores. The IHP produced many teachers, a few farmers, numerous marriages and friendships, a wave of religious awakening and conversions, primarily to Catholicism, some of whom became priests, monks, religious sisters and one bishop.

Mr. Senior was reluctant to respond to the many requests to prepare a list of children’s books because there were so many good choices (a thousand he estimated) that to name a hundred or so could give the impression that these titles were definitive and superior to all the rest. In fact, at the top of his original typed list was the warning in capital letters not to reprint, for private circulation only. The request was not honored and Senior’s list of what he called the Good Books (necessary to be read before reading the greatest and loftiest books, collectively referred to – in similar lists of great classics -as the Great Books) was later included in one of his own books and has become widely available and regarded as helpful in that it groups the reading levels for these classics according to stages of growth and development by approximate age, rather than the more restrictive and mechanical grade levels.

Our list departs from Dr. Senior’s original, lengthier list by excluding those selections no longer in print. We have also added C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series and J.R.R. Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings trilogy for reasons which are articulated in the appended article. Due to persistent parental requests we have added grade level suggestions simply as rough approximations.

To this we believe it is important for our audience to consider some practical considerations in approaching reading and a reading schedule for the Good Books.

Parents who want to teach their children to read often seek information about the best way to proceed: phonics or sight-word methods? We recognize that parents and children have found value in both approaches; in fact, when asked we always say to parents simply to follow the way that seems best to achieve literacy for their children.

Parents who want to teach their children to read often seek information about the best way to proceed: phonics or sight-word methods? We recognize that parents and children have found value in both approaches; in fact, when asked we always say to parents simply to follow the way that seems best to achieve literacy for their children.

From an objective, research-based perspective, however, it does appear that phonics programs for reading have an edge on improving skills in learning the sounds of the alphabet and rendering them into words. On the other hand, sight-readers tend to start reading faster but, it is said by its opponents, these early readers lack the skills to learn or “sound out” words outside their controlled vocabulary. And, there are significant examples on both sides of the “reading wars” issue of children who have learned to read successfully with either phonics or with the various whole-word approaches. As if to add to the confusion, there is another class of children who simply learn to read without formal phonics or sight-word methods and neither parents nor teachers nor specialists are exactly sure how this feat was accomplished. There is one constant that runs throughout the success of all reading programs: children who are read to from the earliest years on tend to be early and good readers.

In general, however, the research appears to indicate that phonics based programs are more effective in teaching skills to understand the sounds of our alphabet and from there to form words. This, in turn, promotes reading confidence and the ability to sound out new words using the phonetic skills.

The length of the classic children’s books ranges from roughly a hundred to eight hundred pages (e.g., some of Dickens), averaging about two hundred pages. We suggest what we believe is a reasonable goal: to read one book every two weeks, thus averaging twenty pages or so a day, excluding weekends if one chooses. Of course, it is not possible to keep this schedule with frequent television viewing or Internet browsing and chat.

We believe that students can increase their pace of reading by increasing the movement of their eyes over the words, taking in more of the sentence, but also slowing down when they begin to lose comprehension. In this way all students can increase the pace of their reading at least to some degree; however, this is not necessarily an endorsement of “speed reading” methods, and the boundaries for increasing one’s reading pace will always be when the individual reader begins to lose comprehension, then it is time to stop just short of that increased pace. The Good Books are excellent material upon which to conduct these experiments on increasing reading pace because unlike some of the Great Books they are not treatises in philosophy, science and theology, being mostly stories and novels. But a more important reason to read the Good Books listed here, and to read them preferably when young, is to prepare the imagination and intellect for the more challenging ideas of the Great Books. It is not a flippant comment to say that a person grounded in the rhymes and rhythms of Mother Goose has also cultivated the senses and the mind for the reading of Shakespeare.

Since both Mother Goose and William Shakespeare are among the great poets, and incidentally were Renaissance contemporaries, they also remind us that it would be an inexcusable omission not to give special mention to poetry as part of the collection of children’s literature.

Since both Mother Goose and William Shakespeare are among the great poets, and incidentally were Renaissance contemporaries, they also remind us that it would be an inexcusable omission not to give special mention to poetry as part of the collection of children’s literature.

Poetry or verse is the unique expression of language that reveals truths and mysteries of life. By the poet’s ever ranging and focusing vision on life, when he speaks he celebrates whatever his muse has drawn him to embrace. It has been said that all poetry is about love in some way, seeking it, having it, or losing it. A good deal of the poems of the nursery and early childhood are about having love, even in the so-called nonsense poetry there is a light-hearted delight that comes from a loving, and lively, heart. And, there are poems of loss that appear in the nursery poems of Mother Goose and Robert Louis Stevenson where the sad times of childhood prepare us for the heartbreaks of adolescence and youth. Love, joy, sorrow, even anger, are all suited to the poet’s voice as he celebrates our moods and emotions and most of all our wonder at the wonder of being alive.

Clear, lively prose is what we want for the narrative mode of stories, but compression and images and precision is the language of poetry, its rhythms and its rhymes, make the poem’s recreated experience more memorable, more interior, more ours. The poet’s gaze into the interior of his subject and diligence and inspiration in finding just the right words also helps us see the world, ourselves and others in a new, yet familiar way and above all more thoughtfully.

Though reading and memorizing poetry is its own reward, to do so in childhood creates a language-rich foundation that supports not only future literary appreciation but increases reflective abilities toward all the subjects of the curriculum. How so? Because becoming familiar with poetry builds the habit of looking beyond the surface and seeing connections between what first appeared as dissimilar ideas or objects. This is the habit of metaphor, that is, the mind beginning to see similarities between what at first appeared to be dissimilar objects and ideas. This is why poetry was always a part of the foundational Trivium, the essential three courses of the medieval liberal arts curriculum, rooted in the classical education of ancient Greece and Rome.

Taken together, the poetry and prose of the best of children’s literature produce not only superior academic results but a self-satisfying experience of living closer to the truth of things, of being more connected with creation and mankind.

Such a claim that the Good Books are the “best” sometimes gives rise to the question: why are there no contemporary titles in your list? What about Harry Potter, for example? Apart from the controversy surrounding the moral ambiguities of the Harry Potter series of books, it is doubtful that such material that depends so heavily on the bizarre and fantastic, with the absence of a dominant theme of human virtue is enough to provide the essential quality of a classic: endurance. Characteristically, “fad” best selling books come and go rather quickly compared to the staying power of, say, The Wind in the Willows, Robin Hood, and, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, that stay in print and are produced in film and stage versions decade after decade, century and century in some cases. So it is not an unusual fact, for example, that in 1955, Scuffy the Tugboat by Gertrude Crampton was a national best selling children’s book, a title and author not completely, but virtually forgotten today. It is not easy to say exactly why one book remains popular regardless of cultural changes while many, many others perish in the recycling bin. Whatever that special appeal the classic book possesses, it acts as a universal voice that speaks to each generation, and each generation and another and another continues to listen and is pleased.

Yet it cannot be denied that modern and contemporary children’s literature has created a large presence in schools, bookstores, libraries and sometimes in the film industry. Since the 1940s, the books of Dr. Seuss have remained in print and in use. For a time titles such as The Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, and, Hop on Pop were used as substitutes for the standard early readers and certainly the playful rhymes and rhythms were a welcome respite from the Dick and Jane type look-say readers. But the Dr. Seuss phenomenon and the explosion of books for children that followed this revolution, began to edge out the classics on book shelves in stores and school libraries; and ideologically the treasury of books from Mother Goose to The Scarlet Pimpernel have come to be considered hopelessly old fashioned and no longer relevant. For these reasons alone the list of books here does not include contemporary or “popular” fiction for children. Furthermore, there will always be books that catch the reading public’s attention, that come and go, and readers of all ages can always sample these books if they are curious about their contents. But what if we were to lose the classics by neglect or deliberate rejection, which convey the roots of our culture?

Yet it cannot be denied that modern and contemporary children’s literature has created a large presence in schools, bookstores, libraries and sometimes in the film industry. Since the 1940s, the books of Dr. Seuss have remained in print and in use. For a time titles such as The Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, and, Hop on Pop were used as substitutes for the standard early readers and certainly the playful rhymes and rhythms were a welcome respite from the Dick and Jane type look-say readers. But the Dr. Seuss phenomenon and the explosion of books for children that followed this revolution, began to edge out the classics on book shelves in stores and school libraries; and ideologically the treasury of books from Mother Goose to The Scarlet Pimpernel have come to be considered hopelessly old fashioned and no longer relevant. For these reasons alone the list of books here does not include contemporary or “popular” fiction for children. Furthermore, there will always be books that catch the reading public’s attention, that come and go, and readers of all ages can always sample these books if they are curious about their contents. But what if we were to lose the classics by neglect or deliberate rejection, which convey the roots of our culture?

Finally, a reminder: Dr. Senior was the first to say that his list of books for children was far from definitive, that on another day he might make a different selection in some cases as he suspected alert readers would as well.. Also, he said he certainly could be wrong about the reading age and the selected books for that group; the parent or teacher should remain experimental allowing the child to discover their own level of reading challenge and appreciation. Such was the reasonable spirit that informed all of John Senior’s life and teaching; it is the same goodwill we wish to impart to the readers of this book.

CHILDREN’S LITERATURE INTRODUCTION

The best of children’s literature is simply good literature that anyone, child or adult, can enjoy. It is impossible to imagine that Aesop’s Fables, The Household Tales of the Brother’s Grimm, or Treasure Island, would not be found delightful by adults as well as children. The poems and stories that were once enjoyed in wonder and delight in youth are now viewed in maturity in their truth and wisdom.

For many contemporary books marketed for children, this is not the case; they are often silly and regard the child as a kind of simple toy, or the stories are laced with special interest, social agendas, and in some cases the material is inappropriate or simply morally offensive.

For many contemporary books marketed for children, this is not the case; they are often silly and regard the child as a kind of simple toy, or the stories are laced with special interest, social agendas, and in some cases the material is inappropriate or simply morally offensive.

The illustrations for many contemporary children’s books are gaudy while the human and animal figures are grossly distorted. This is not to say there are not authors of children’s literature writing serious and significant material today – and talented and traditional illustrators – there are both. But with the exception of specialty stores that carry children’s books written and illustrated in the more traditional mode, the classic books for children occupy a small space on the shelves of the big book stores.

And yet, the best of children’s literature is still in print and can be ordered from booksellers or found in libraries; on the Internet new and used copies of classics can be purchased usually for reasonable prices. Perhaps the audience for these good books for children is smaller now but the poems and stories that nourished children and pleased adults for centuries refuse to go away; their appeal remains irresistible and their imaginative experience is memorable for a lifetime. Why is this so? To ask this question another way, what makes a book a classic?

Because literature is an art it can never be understood as if it were a science like mathematics. In the end, there will always be an element of a poem’s charm or a story’s success we will not be able to explain in rational terms as if we were explaining why one engine works better than another. But, we can say the following about classic literature: the classic poem or story not only says something true and ultimately good about the nature of life and human beings regardless of time or place, race or religion or circumstances; it says it in a way that is delightful and memorable. The literary work not only tells a story and imparts knowledge in a unique way, the art of the tale or the poem is an aesthetic experience. (Aesthetic is from a Greek word that has to do with feelings and pleasurable emotions. When we go to the doctor and receive an anesthetic we are being made temporarily not to feel so a particular examination or operation can be performed without feeling pain.)

In this realm of beauty found in the pleasure derived from what is read, not all the story’s charm is revealed at the first or second or even after several readings. As we know, most children beg to hear the good poems and stories again and again so they can continue to experience their delight and even their surprise. At least, that’s one reason why we think children do this though we must repeat that there is also something mysterious and unknowable why poems and stories affect us the way they do. We can profit a great deal by talking about them with friends and family, but in the end we can never explain why it is exactly that we continue to admire them. Some teachers of literature are impatient with students who simply say after reading a story or poem, “I like it, but I’m not sure why.” Of course, some discussion of the material is appropriate, but without our undisturbed, first reactions of pleasure and delight with literature there can be no further appreciation. We remember that to analyze means to take apart. But will we be able to put it together again?

Even though classics are old, their themes and the delight they give are ever young. A famous poet once said that poetry is news that stays news. This is true of all classic literature from Aesop to Shakespeare. So, these good books contain something true, unchanging and good about life; and dramatize these truths for us in a pleasing and memorable way. Before elaborating on the definition of a classic book let’s look at the historical and cultural environment that in part undermined the dominant themes of the true and good found in the Good Books.

The literary, philosophical and religious climate following World War I was not friendly to traditional beliefs about the essential goodness of man. Perhaps this can be understood from a psychological and sociological perspective given the carnage of modern warfare and the disruption of nations. The modern era has also seen the exposure of corporate and political ambition, the corrupt views of teachers in schools and universities, the scandal displayed by public leaders and even some clergy are signs of a world’s critical illness still very much with us in the 21st century.

Literary themes that emerged from this era tend to be melancholy and dark; characters are often despairing, violent, or overwhelmed. Frequently, stories, poems and novels of the modern era lack any objective moral center of gravity and often end either in ambiguity or tragic absurdity. These times have also seen an alarming increase in escapist and fantasy literature that lead the reader further and further away from reality.

Literary themes that emerged from this era tend to be melancholy and dark; characters are often despairing, violent, or overwhelmed. Frequently, stories, poems and novels of the modern era lack any objective moral center of gravity and often end either in ambiguity or tragic absurdity. These times have also seen an alarming increase in escapist and fantasy literature that lead the reader further and further away from reality.

In spite of the discouraging landscape left by this phenomenon called modernism, the classic books of childhood and adolescence, the Good Books, continue to refresh the air of life. This imaginative experience is more important now than ever, not only for children who are forming their ideas about the world and their lives, but for adults who can rediscover and in a way relearn essential truths once seen clearly in childhood.

To say these classic books are true and good does not mean they do not contain evil; the stories of Grimm and Anderson for example would be nothing without the presence of cruel adults and disobedient children. Sometimes it appears the evil characters triumph over the good when we have a sad or tragic ending. But we would never recognize such characters and endings as sad if it weren’t for the story’s central sympathy with the good. In fact, it is only a life centered in the good and the beautiful and the true that recognizes and mourns the presence of their opposites. In this way, the presence of cruel stepmothers, witches and ogres, giants and monsters are true in that they are representative of evil present in the world. In an early version of Little Red Riding Hood the little girl, disobeying her mother’s warnings, dallies on her way to visit her sick grandmother and stops to chat with a stranger, a barely disguised wolf. The story’s conclusion is clear: the little girl is devoured by the wolf. The end!

So one thing we can say about classic stories is that they arouse our sentiments, in the case of the Little Red Riding Hood, fear and pity; but they are not sentimental in the way the Walt Disney versions are rewritten and presented. . The famous Hollywood rendition of Pinocchio, for example, presents a mischievous little puppet who yearns to be a real boy. The original story by Carlo Collodi reveals a wooden puppet that is cruel and violent between short-lived lapses into self-pitying remorse. In one of the early chapters, Pinocchio picks up a large mallet and smashes the Cricket; nor is he sorry. He continually betrays the love and trust of Gepetto to the point of nearly breaking the old man’s heart. The real story of Pinocchio by Collodi is one of conversion, a replacing of a wooden heart with a human one that has learned to love. It is this element of virtue, or the alarming lack of it, that is characteristic of a classic book though the best of these books never moralize or preach life’s lessons to us. They show them and we feel with, that is, we sympathize with them. It is this moral depth of the story, more mature than the thinned out popular versions, that elevates the original tale above the realm of mere entertainment and places it with the great stories that are both true and good.

The second element of a classic story or poem, that the work is delightful and pleasing and can be experienced over and over, is not separate from the fact that it is true and good. A work of art can never be systematized, analyzed, taken apart, classified and labeled and put back together again – neither could Humpty Dumpty! Rather, we say a classic work of art, be it a painting, sculpture, musical composition, or literature, is experienced as an integrated whole. It is difficult to say exactly why a piece of literature possesses the quality of lasting pleasure, but it has something to do with this unity where the characters, the plot, the dialogue, beginning, middle and the end, combine in such a way as to proclaim that the story or the poem could not have been written in any other way. There is nothing we would change. Just as Goldilocks found one bowl of porridge “just right” without defining exactly what that means, so too we know when we finish a good story such as Goldilocks and the Three Bears or Jack London’s Call of the Wild, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, or Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, that we experienced a delight in the telling that we would desire others to experience again and again. This ongoing popularity of the classics is the long view afforded by the Good Books. These titles and perhaps a thousand more stay in print year after year, in some cases century after century, whereas it is likely the best seller of today will be recycled paper for tomorrow.

The second element of a classic story or poem, that the work is delightful and pleasing and can be experienced over and over, is not separate from the fact that it is true and good. A work of art can never be systematized, analyzed, taken apart, classified and labeled and put back together again – neither could Humpty Dumpty! Rather, we say a classic work of art, be it a painting, sculpture, musical composition, or literature, is experienced as an integrated whole. It is difficult to say exactly why a piece of literature possesses the quality of lasting pleasure, but it has something to do with this unity where the characters, the plot, the dialogue, beginning, middle and the end, combine in such a way as to proclaim that the story or the poem could not have been written in any other way. There is nothing we would change. Just as Goldilocks found one bowl of porridge “just right” without defining exactly what that means, so too we know when we finish a good story such as Goldilocks and the Three Bears or Jack London’s Call of the Wild, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, or Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, that we experienced a delight in the telling that we would desire others to experience again and again. This ongoing popularity of the classics is the long view afforded by the Good Books. These titles and perhaps a thousand more stay in print year after year, in some cases century after century, whereas it is likely the best seller of today will be recycled paper for tomorrow.

The reason for the persistent presence of the classics of children’s literature is not the result of marketing techniques and expensive advertising campaigns. These books continue to be read because children and adults discover that what they reveal about our lives and our world is not just true at a certain period of time or in a certain location for a particular group of people, but are always true, everywhere for everyone. Another reason for their appeal rests on the intuitive knowledge of the true and good everyone who encounters them share, who discover it is a better and higher thing to enjoy and be schooled by a work of art than to analyze it. Since the themes of the stories reveal timeless truths about the human condition, from the humorous to the tragic, we see that one of the marks of a classic is its universal appeal. We experience a sense of unity with nature and human nature when we give ourselves to the classic stories and poems of the Good Books. There is a sound reason and one not difficult to discover why Aesop, Huckleberry Finn, the works of Homer and Shakespeare continue to be translated into nearly every language in the world.

But we must admit our modern times have not been encouraging for reading and conversing about what we have read. Conversing is an aspect of leisure that naturally accompanies the act of reading that has been terribly undermined by the visual and to some extent the audio stimulants of contemporary culture. It has become commonplace for reading enthusiasts to recognize and blame television for luring children and their parents away from reading books and conversing about them, and instead spend their free time staring into the bright and flashy electronic window of movement and color accompanied by high fidelity and stereo sound from the TV set and now the computer screen.

Individual reactions will vary to television viewing and the varieties of video experience: computer screens, DVDs, and movies in theaters. It seems that the less frequent the video experience, children are able to take or leave the electronic stimulation of the eyes and continue to cultivate their imagination and intellect through reading good books. But the more children who watch electronic images with super sound instead of reading, the more they not only lose the ability to enjoy stories, histories, and poetry, but they also lose interest in conversing about much more than the latest news in the world of popular culture – music, sports, movie and television stars.

Marie Winn in her book, The Plug-In Drug, published in 1977, appeals not only to common sense about the decline in reading in America, but includes data from controlled studies that reveal what occurs in the eyes and in the brain of a child watching television. It amounts to a virtual disconnect with reality. Her thesis was revolutionary when the book first appeared: she said that arguments over content on television are irrelevant compared to the real danger. Eye movement resembles a hypnotic or drugged state and the brain reacts in some respects as if it were asleep when viewing television. It was not simply a discussion about the “bad” programs versus the “good” ones, she said, or the superiority of so called “educational” commercial-free, clever children’s shows that appeared on PBS Television. Winn said that the viewing experience itself was harmful regardless of what was on the screen. The posture, facial expression and the subdued brain activity on one hand, and brain agitation on the other, indicated that television viewing especially for the younger viewer looked more like a drug induced state than a learning experience regardless of the quality of the content. Marshall McLuhan warned of the same danger, summarized in aphorisms such as “The medium is the message,” and “With telephone and TV it is not so much the message as the sender that is ‘sent’.”

The implications for social life and reading were obvious. With extensive viewing healthy family life deteriorated where the children became remote from the family circle. Deprived of essential real-life experiences when it came to reading either informational or imaginative material the child lacked sensory and intellectual memories of reality to form images and ideas from what they were reading. Winn also cites studies that strongly suggest links between the video experience and forms of dyslexia and so-called ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder).

Book publishers and authors continue to produce more materials for children, but since the television and video screen revolution many of these books are written in language far below age level and illustrated with garish colors and distorted figures (such as those used by Theodor Geisel a.k.a. Dr. Suess and Maurice Sendak) to compete with the flashy visual displays on the electronic screen.

This technological distraction to reading used to be confined to the home where there was one television set for the family. Now there are often several sets throughout the house, stereo players, Walkmans, iPods, computers, telephones and cell phones so that each home has become an electronic village. At most schools, the video and electronic experience continues with computers and televisions in the classrooms and (ironically!) in the library. Every moment spent with these devices at home or school is lost time the student could have been reading good books and talking about them with their classmates and teacher and preparing to write about the book’s themes and characters.

This technological distraction to reading used to be confined to the home where there was one television set for the family. Now there are often several sets throughout the house, stereo players, Walkmans, iPods, computers, telephones and cell phones so that each home has become an electronic village. At most schools, the video and electronic experience continues with computers and televisions in the classrooms and (ironically!) in the library. Every moment spent with these devices at home or school is lost time the student could have been reading good books and talking about them with their classmates and teacher and preparing to write about the book’s themes and characters.

Students, parents and teachers sometimes ask what the difference is between reading books onscreen, such as, Robinson Crusoe, certainly one of the Good Books, and reading the same story on the printed page between the covers of a book. The answer requires that we remind ourselves of who we are: human beings, the philosophical or religious definition of which states we are a composite of a body and a soul. That means we react to the world and things that come our way with both our external senses and or internal senses. We use our eyes that focus on three dimensional reality, our ears that receive sounds either heard aloud or in the silence of our minds, and the sense of touch that feels the heft and surfaces, edges and width of objects (such as books). Each of these external senses working together inform our ideas of things: are they pleasant or unpleasant, bright or dark, warm or cold? Finally, in the mysterious integration of body and soul a conclusion is reached sometimes quickly, sometimes after repeated experiences, that a particular thing, person or place is either good or bad for us. In this way all our judgments about things become ethical or moral because value is assigned to life’s experiences based on whether they are good or bad. But it all begins in the realm of the senses – all of it.

Consequently, the sensory experience of reading or listening to a story involves not only more of the powers of the human being but as a result engages our sense of moral evaluation more keenly. When the sensory and mental powers are focused on the content of the Good Books then our sense of the good, the true and the beautiful are increased even more since the culture of these stories and poems are saturated in either the ethical perception of the modern world or the ancient world or the Judeo-Christian revelation of Western civilization. The flat surface of a computer screen where text floats, suspended in cyber space, has the impression of if not actually being close to non reality, of not quite existing as well as giving rise to the debate: is such protracted (average of 5+ hours per day) onscreen reading, as well as television viewing, detrimental to good vision?

To read the Good Books is to participate in the great tradition of learning through delight and wonder that leads to wisdom which is to discover and do the good which is the heart’s deepest longing, to be united to the good, the true and the beautiful which is happiness on earth. Without pedantic “teaching or preaching”, every Aesop Fable is a dramatized story of the virtues, prudence, justice, courage, and temperance, often instructing by the defect or excess of the virtue. We really do not need the “moral lessons” at the end of these perfect stories – attentive readers see their meaning integrated within all the elements of the story, not as a simplified afterthought.

The books read when students are older, for example, those by Louisa May Alcott, or Robert Louis Stevenson, or Mark Twain, portray characters memorable for their bravery or cowardice, compassion or bitterness, prudence or bad judgment, impatience or long suffering. And yet for all the positive things we can say about the Good Books as instruments of cultivating the imagination upon truth and forming the character upon goodness there is another appeal to the reader that resides in the experience of beauty that is characteristic of all art, a mysterious dimension of wonder and pleasure that is impossible rationally to explain. It is real and certain and draws our attention to itself, but we are at a loss to describe it. The ancients attributed this allure to the presence of the Muse, a mysterious source of inspiration for the author and the reader. The invisible reality of the Muse has continued to be acknowledged from the classical Greek dramatists to the modern American poet Robert Frost.

All these things, delight, wonder, virtue, and inspiration simply are not present in the majority of the so-called children’s literature of today. Social themes such as divorce and alternative life styles; political relevance topics such as concerns over the rain forest, global warming, and racial and gender equality dominate children’s literature and are often used in social studies classes. These may indeed be relevant socially and politically but they have no Muse, that is, there is nothing to admire and love about the characters since they appear in the story merely as figures to act out whatever agenda is being promoted. Furthermore, such stories will not achieve a universal theme, a victory or failure based on the unity of all human beings, but whose action and outcome is confined to one particular circumstance that could or could not apply to others.

All these things, delight, wonder, virtue, and inspiration simply are not present in the majority of the so-called children’s literature of today. Social themes such as divorce and alternative life styles; political relevance topics such as concerns over the rain forest, global warming, and racial and gender equality dominate children’s literature and are often used in social studies classes. These may indeed be relevant socially and politically but they have no Muse, that is, there is nothing to admire and love about the characters since they appear in the story merely as figures to act out whatever agenda is being promoted. Furthermore, such stories will not achieve a universal theme, a victory or failure based on the unity of all human beings, but whose action and outcome is confined to one particular circumstance that could or could not apply to others.

There are also other modern themes that have entered juvenile fiction: loneliness, alienation, failed friendships, themes directed toward early adolescent girls in particular. Popular fiction for adolescent boys is dominated by fantasy and the fantastic, and violence, exploiting boys’ natural inclination for action and adventure. The stories and novels for this age group are written and illustrated almost entirely for visual excitement that creates a state of stimulation much like the viewing of video games and “action-adventure” movies. In this literature there is no depth of character upon which to reflect and very little moral distinction between the hero’s use of force to win the day and the villain’s shear barbarianism.

Again, it is very important to repeat that this overview of the current state of children’s literature is by necessity a generalization because these features and trends are generally true; however, there are writers and illustrators of children’s books today who are innovative and place their stories in modern settings, yet compose their themes and illustrations within an artistic and ethical tradition of literature for younger readers.

Even though reading the Good Books are their own reward, that is, their worth is found in the delight and knowledge they give, not in material reward; it is also true that a grounding in this literature cultivates our emotional and mental life to receive the ideas and questions presented by the Great Books of Western civilization that begin with such authors as Homer, Euclid, Plato, Aeschylus, and Aristotle. In other words, if a child has been well nourished on Mother Goose and Robert Louis Stevenson, he or she is ready to read Shakespeare.

A student thus nourished passes from reading the Good Books to the first Great Books generally somewhere between the end of the elementary experience and the beginning college years. However, firmly assigning a Good or Great Book to a grade level fails to observe the emotional and mental “ages” that can vary quite a bit. Flexibility based on the ability of the student should determine at what time a particular book is read. Unlike empirical science, teaching the Good Books is experimental, like an art, where the rational faculty of the child is not the main focus, but the intuitive, the emotional, imaginative and the sensory dimensions of his being are brought into play.

A student thus nourished passes from reading the Good Books to the first Great Books generally somewhere between the end of the elementary experience and the beginning college years. However, firmly assigning a Good or Great Book to a grade level fails to observe the emotional and mental “ages” that can vary quite a bit. Flexibility based on the ability of the student should determine at what time a particular book is read. Unlike empirical science, teaching the Good Books is experimental, like an art, where the rational faculty of the child is not the main focus, but the intuitive, the emotional, imaginative and the sensory dimensions of his being are brought into play.

Education by the Good Books that leads to the Great Books, enriching the soil of the soul’s higher faculties achieves something greater than cultivating literate and literary-minded students – it passes on the best of our culture. And what has been that culture? It is the best of what man can achieve for civilized society, it is excellence of character by which we measure our goodness and our faults, it is the civil of civilization which requires a life based on principles rather than whim in relationships in the family, government, economy, labor and leisure, and religion. It is freedom to enjoy the life of the mind as well as the good of the body; it is the hope to build society upon moral principles whose very atmosphere encourages its citizens to excel as individuals within a community of like minded men and women regardless of ethnicity, race or cultural differences.

Think of an education without the traditional nursery poems, A Child’s Garden of Verses, or Treasure Island, Little Women, and The Secret Garden, and how much exposure to humanity in all its variety would be missed. Without the literary mode that as Aristotle said not only instructs but delights, education would not be worthy of the name. Note well that all totalitarian regimes in the past and in our time remove first from education all books of poetry and fiction, books that portray the breadth of the human spirit. By reading these books that portray us at our best and sometimes at our worst, we are united in a common bond of understanding of what it means to be human and thereby create in us a sympathy and a tolerance for the foibles of mankind and an abiding admiration for our ability to be loving, courageous and kind. In the end, this is education’s purpose, this maturing of our humanity, and the children’s classics – the Good Books – are certainly an essential means of conveying this noble work.